The Straits Times (2 August 202)

The ear is more delicate than you think. Once the hair cells inside are damaged, they don’t regenerate. Hearing loss is also linked to dementia risk.

And just like that, my house became quieter.

Last week, my mother was fitted with a pair of hearing aids.

Normally, when I take a shower in the bathroom next to her bedroom, I can hear her TV blasting away. But that evening, I could barely hear a thing.

Curious, I went in to check.

"Are you okay? Can you hear the TV?"

"Yes,” she said. "It’s quite loud.”

Her answer made me pause and wonder: Is my own hearing slipping? Her TV was now softer than what I’m used to myself. At 90, my mother’s hearing has served her well, and it’s only in the last two or three years that we noticed changes.

It began subtly. She started saying "huh?” more often and we would have to repeat ourselves.

Then the volume of her TV started to creep up. "Too loud,” I would complain, turning it down.

At family gatherings, she seemed increasingly disengaged, often ignoring questions directed at her.

"I can hear,” she once told us, "but I don’t know what people are saying or why they are laughing.”

Concerned, we finally took her to an ear and throat specialist in July. The diagnosis: age-related hearing loss, medically known as presbycusis. This condition can’t be reversed but hearing aids can help manage it.

That’s when I learnt that hearing loss isn’t just about volume. It is also about speech clarity. Hearing aids don’t just make sounds louder, they also make them clearer.

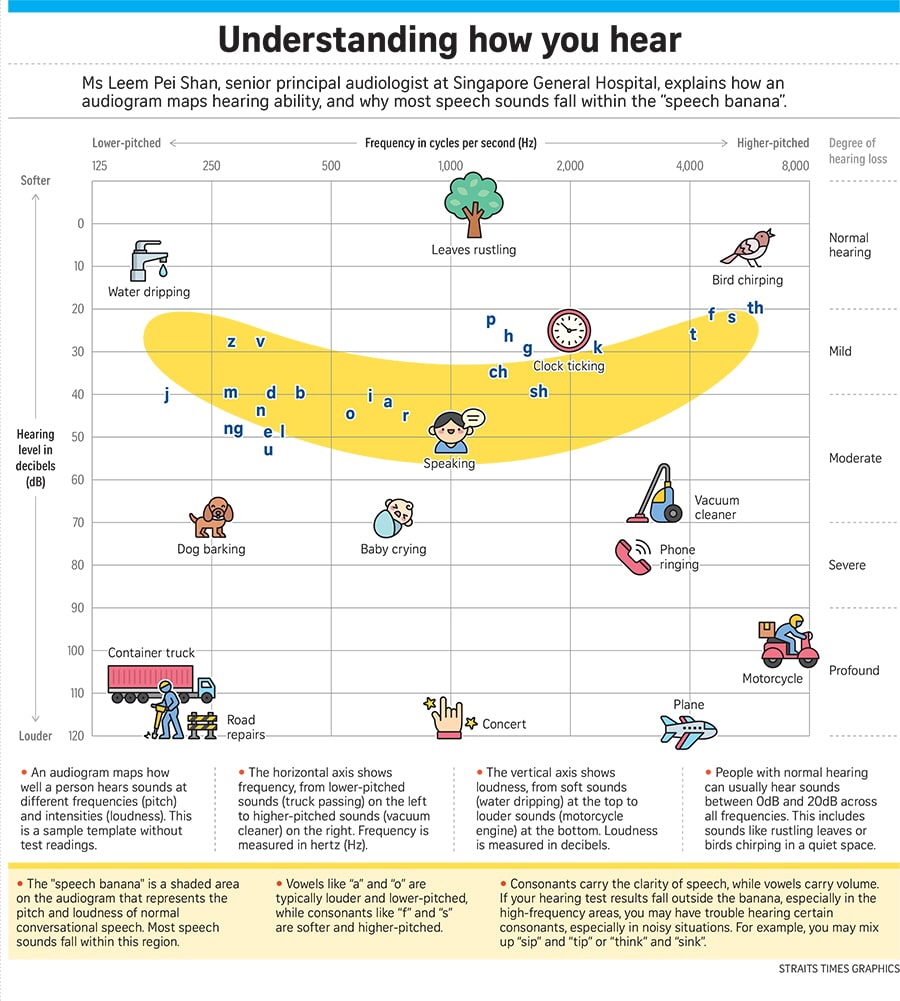

Different sounds have varying loudness and frequency characteristics, explains Ms Leem Pei Shan, a senior principal audiologist at the Singapore General Hospital (SGH).

For example, vowels like "o” and "a” are generally louder and lower in frequency, whereas consonants such as "f,” "s” and "th” are softer and higher-pitched.

If hearing loss affects higher frequencies – as is common with presbycusis – you might struggle to distinguish certain sounds, especially in noisy environments.

This can cause confusion between words like "sip” and "tip” or "think” and "sink”.

Hearing loss can range from mild to profound and impacts everyday life in different ways.

Ms Chua Xin Ning, a senior audiologist at the

department of otorhinolaryngology at Tan Tock Seng Hospital, says that missing high-frequency sounds may mean someone doesn’t hear a bicycle approaching from behind, or may fail to notice that it’s raining when laundry is left outside.

Dr Vanessa Tan, a senior consultant at SGH’s department of otorhinolaryngology, says that about 10 per cent of people aged above 60, and 35 per cent of those above 80, suffer from hearing loss. Her advice: If you’re over 60, get your hearing tested.

A basic hearing test usually begins with a quick, painless check of your ears to look for blockages or other issues. Next, you sit in a soundproof room wearing headphones and listen to tones at different pitches and volumes. Each time you hear a tone, you respond by pressing a button or raising your hand. The results are charted on an audiogram, a graph which shows your hearing ability across different frequencies.

There’s also the Hearing Number, a simpler way to understand your hearing than an audiogram. Developed by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, it tests the softest speech sound you can hear in each ear, and the lower the number, the better your hearing. The free test can be taken on the Hearing Number smartphone app using headphones.

"Our hearing number will change over time and it’s part of ageing,” Ms Leem says. "The number matrix can help people visualise and monitor their hearing and when it is time for them to seek help.”

While age-related hearing loss isn’t reversible, it develops gradually. This slow progression allows for early detection and treatment to manage it.

Singaporeans aged 60 and above can get their hearing tested as part of Project Silver Screen, a nationwide screening programme covering vision, hearing and oral health. It costs $5 or less and is offered at community venues. Here are six other things to know about presbycusis.

HOW DOES THE EAR WORK?

To understand why hearing loss occurs, it is helpful to know a bit about how our ears function. The ear has three main parts:

- The outer ear, including the ear canal, which collects sound.

- The middle ear, where tiny bones (ossicles) amplify sound vibrations.

- The inner ear, which houses the cochlea and the vestibular system.

The cochlea is a spiral-shaped organ that converts sound vibrations to nerve signals the brain can understand. The vestibular system provides the brain with information about motion, head position and spatial orientation, helping you maintain your balance.

WHAT TYPES OF HEARING LOSS ARE THERE?

There are two main types of hearing loss – conductive and sensorineural.

Conductive hearing loss occurs when sound can’t properly travel from the outer ear to the inner ear. This can be due to earwax, ear infections, eardrum damage or problems with the bones in the middle ear.

Sensorineural hearing loss is due to damage of the cochlea or nerve. The most common cause is ageing but it can also be congenital or due to excessive noise, certain medications or inner ear tumours. Treatment depends on the cause and may include medication, surgery, hearing aids or implants.

WHAT HAPPENS IN AGE-RELATED HEARING LOSS?

Inside the cochlea of the inner ear are tiny sensory cells called hair cells. They are not actual hairs but microscopic cells with hair-like projections called stereocilia. When sound vibrations enter the ear, these stereocilia move and convert the vibrations into electrical signals. These signals are sent to the brain, which interprets them as sound.

Dr Tan says that with repetitive movement over the years, hair cells degenerate with time. These hair cells do not regenerate, which means any hearing loss resulting from their deterioration is permanent.

The cochlea has different sections that pick up different pitches, or frequencies, of sound. The hair cells in the basal turn of the cochlea – the part closest to the middle ear – detect high-frequency sounds and are typically the most vulnerable to damage, says Dr Tan.

Patients with age-related hearing loss often complain of loss of speech clarity, especially in noisy spaces. Other common symptoms include fatigue from straining to hear, a ringing sound in the ears (tinnitus), having to rely on lip-reading and asking others to repeat themselves. Dr Tan adds: "Patients often don’t even know they have hearing loss and it is their family that complains that the TV is too loud or that they have to shout at the patient.”

Dr Paul Lock, a consultant at the department of otorhinolaryngology at Tan Tock Seng Hospital, says presbycusis is symmetrical (both ears), gradual and is not related to other symptoms such as ear discharge, pain or vertigo. There is strong evidence that it has a significant genetic component, he adds.

HEARING AND THE DEMENTIA LINK

Beyond communication, hearing loss also affects overall brain health.

In a study that tracked 639 adults for nearly 12 years, researchers from Johns Hopkins found that mild hearing loss doubled dementia risk, moderate hearing loss tripled the risk, and people with a severe hearing impairment were five times more likely to develop dementia.

The Lancet Commission on dementia prevention ranked hearing loss as the most important modifiable risk factor for dementia, points out Dr Tan. A recent study published in Jama Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery showed that hearing loss was associated with increased dementia risk especially among people not using hearing aids. "This finding suggests that hearing aids might prevent or delay the onset and progression of dementia,” she says.

Doctors say hearing loss may affect brain health in several ways.

First, hearing loss can force the brain to work harder to process sounds, potentially diverting cognitive resources away from other crucial functions like memory and thinking. Second, people with hearing loss have difficulty understanding conversation and may withdraw from social activities, which is a known risk factor for dementia. Lastly, there might be a shared biological cause that impacts both hearing and cognitive function. Dr Lock says that even if a person already has dementia, keeping them oriented to their surroundings is important.

"Having good hearing and constantly being engaged and socially oriented will logically help to slow the deterioration.” He adds: "Besides dementia, patients who have hearing loss are often socially withdrawn as they are unable to engage in meaningful conversation or are too embarrassed to do that. This leads to poor psychosocial health and emotional well-being.”

WHY IS LOUD NOISE SO BAD FOR THE EARS?

Loud noise is dangerous because it damages the delicate hair cells inside the cochlea.

Dr Tan warns: "Avoid sustained loud noise exposure. If your ears are painful or experience tinnitus following noise exposure, it is a sign to quieten down.”

To put noise levels into perspective: a whisper measures about 20 to 30 decibels (dB), a busy restaurant around 70dB to 80dB, and a food blender roughly 85dB. In comparison, a Formula 1 racing car roaring past at close range can reach a staggering 130dB to 140dB.

Even a single exposure to extremely loud noise can cause damage, says Dr Tan. "The duration depends on the sound intensity. The louder the sound, the shorter the time needed to cause noise-induced hearing loss.”

For example, exposure to noise at 85dB for more than eight hours can lead to hearing loss. With every increase of 3dB, the safe exposure time is cut in half. That’s why she recommends keeping volumes at or below 60dB.

However, it doesn’t mean that someone who avoids loud noises can escape hearing loss since genetics also play a role.

As to whether wearing earphones raises your risk of hearing loss, Dr Lock says it is not the sound delivery device that causes damage but volume. "We always recommend avoidance of loud volumes – whether speakers or headphones – and to always take breaks from long periods of listening,” he adds.

WHAT DO HEARING AIDS DO?

Ms Chua says hearing aids are typically recommended for moderate or more serious hearing loss, but can be useful as soon as hearing difficulties start affecting daily conversations or safety.

It’s not uncommon for family or friends to notice early signs of hearing loss before a person does, as they often have to speak louder or repeat themselves, she says. "If you notice an increase in criticism regarding your hearing ability, it is advisable to arrange for a hearing test.”

Dr Lock says hearing aids have complex microprocessors that help to amplify the particular frequency that is missing to the appropriate level. "Unlike spectacles, they are dynamic devices and have a significant level of adjustment and fine-tuning possible.”

He notes that over-the-counter hearing aids are gaining traction, with some consumer devices providing similar functions. "They are, however, limited in function and might not support your hearing if the loss is extensive,” he says.

Prescription hearing aids are custom-fitted and programmed by audiologists following thorough testing and ensure the best sound, clarity and comfort. But they don’t come cheap, as I discovered when my mother was fitted with her pair. Hearing aids range from around $1,000 to $9,000 – and that is just for one ear. A pair of premium aids can cost $18,000. These devices typically last five years.

Ms Leem says prices depend on features. "Higher price doesn’t always mean better results. Basic models may be sufficient for some users,” she adds.

Another hurdle for some is the stigma linked to hearing aids. Many hesitate to wear them because they worry about looking old or disabled. But, as I found out, devices today are much smaller, sleeker and more discreet than the bulky models of the past. Some even look like stylish earbuds. (Tip: black or darker colours look more modern and tech-inspired than skin-tone ones, which can appear medical or old-fashioned.)

You can’t use MediSave for hearing aids, but the Seniors’ Mobility and Enabling Fund administered by the Agency for Integrated Care (AIC) provides means-tested subsidies for Singaporeans aged 60 and above to offset the cost.

Currently, households with per capita household income of up to $2,600 qualify. This will be raised to $4,800 from January 2026 and will include permanent residents.

Seniors who don’t qualify but need help can approach AIC, SG Enable or medical social workers at public hospitals.

As for my own hearing, I had it checked during a recent annual medical screening. It is mostly normal though I have some difficulty hearing very high-frequency sounds at low volumes in my right ear. The doctor said it wasn’t a concern but advised me to protect my ears from loud noise to prevent further decline.

My mother’s experience with hearing loss taught me two lessons.

First, I shouldn’t take my hearing for granted. I should protect my ears from loud noise. For a start, I’ve set the maximum volume limit for my smartphone at 50 per cent. (The World Health Organisation recommends keeping device volume at no more than 60 per cent of the maximum.)

Second, I need to start setting aside money for the day I need hearing aids. And when the time comes, I will wear them because they will help keep dementia at bay – and they don’t look half-bad these days.

Since getting fitted with the hearing aids, my mother has been noticeably chirpier. She adapted quickly, finds them comfortable and barely notices they’re there. She says her own voice sounds a little louder than she’s used to, but the world around her is so much clearer now, even with the TV set to a low volume.